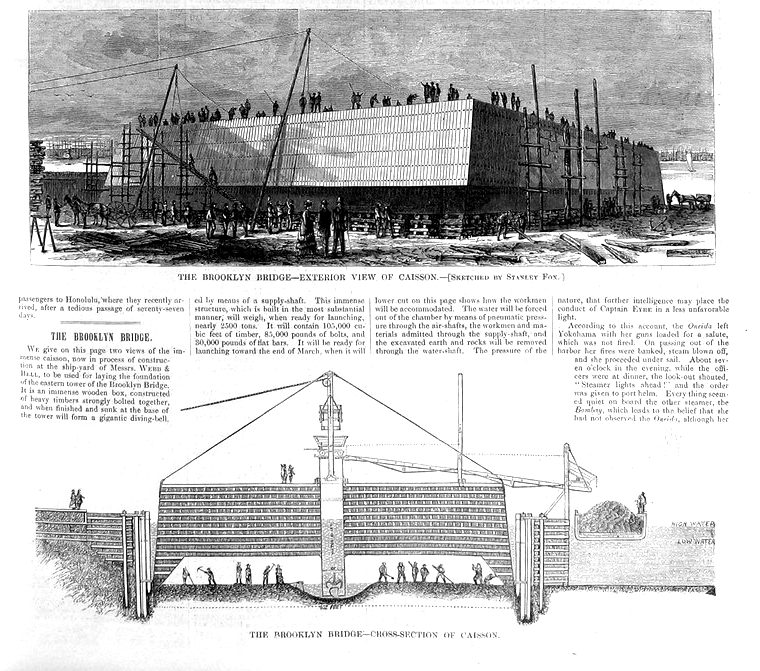

Following up on part 1 and part 2, I want to talk about how the caissons of the Brooklyn Bridge were built, installed, and used. Unlike the 1883 image from part 1 (below), the image above is from 1870, while the work was still going on. I’ve played with the contrast to make the drawings clearer, which had the effect of making the text less clear.

The upper image shows one of the caissons as it was being built at a shipyard on the East River. When I say it was a big wooden box, well it’s a big wooden box. Then again, a wood-hulled ship is also a big wooden box, just open on top instead of on bottom. They were launched into the river like ships, filled with compressed air so they’d float, towed to position, and sunk to the river floor by reducing the airflow. The lower image shows the work shortly after the caisson was put in place. Note that the general floor level inside is the same as outside. Brooklyn is to the left, the bulk of the river is to the right, and the caisson is surrounded by a non-watertight cofferdam of wood piles driven into the river floor. The cofferdam was for protection more than anything else: the East River is a tidal strait with fast currents that change direction four times per day, and the currents could (a) push the caissons around before they were properly seated and (b) might push ships into the caissons. Laborers are digging up the soil floor inside and shoveling the loose material into the pit at the base of the water shaft, from where the clamshell bucket grabbed it, pulled to the top, and dumped it into the chute leading to the little barge off to the right.

The air pressure inside the caisson was kept just slightly higher than the water pressure at the caisson floor elevation, to keep the water out. Water weights a bit less than 63 pounds per cubic foot, so if the caisson bottom was at 20 feet below mean high tide, the pressure inside would be 63pcf×20ft/144psf/psi = 8.75 psi higher than ordinary air pressure of 14.7 psi. We never notice ordinary air pressure, but we notice changes, like a 60 percent increase in it.

The original idea was that the natural course of work, building the stone tower of the bridge on the back of the caisson, would drive the box into the ground, hence the name “cutting edge” for the metal shoe at the base of the walls. In reality (a) the bearing pressure below the shoe was too low because the caisson perimeter was so large, (b) as the box was sunk down into the earth, friction between the sides and the surrounding soil provided a lot of support, and (c) the soil on the Brooklyn side, where the first caisson was sunk, was of varying composition, with boulders big enough to break the wall edge. So the workers excavated the soil below the caisson edges to allow it to sink smoothly.

More to come!

You must be logged in to post a comment.