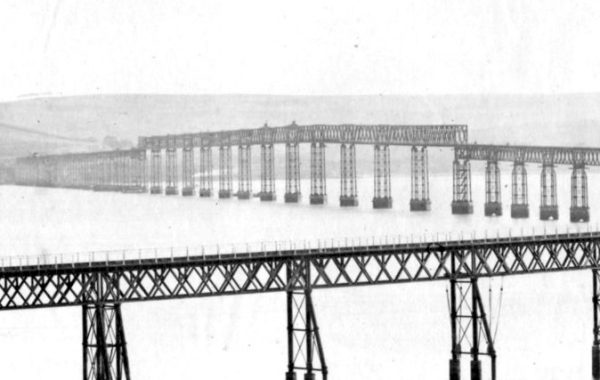

From 1932, a reproduction of a circa-1900 view of the suicide curve on the Ninth Avenue Elevated:

Putting aside the children’s-book feel to the illustration, you can see the same basic structure as in the photo from Monday: columns with a round cross-section (built-up Phoenix columns), bracketed moment connections at the lower tied of beams, and rod cross-bracing between the lower and upper tiers.

There’s one detail that is structurally intriguing, and that is the form of the lower tier beams. The upper tier beams that are not directly supporting the tracks have the same form as well. Those beams are built-up lattices (small trusses, in all but name) and have curved top and bottom chords so that they are quite narrow where they connect to the columns and fairly wide mid-span.

There’s a terminology problem here. They are not “beams” in the load-based sense of “horizontally-spanning members that carry vertical load.” They are “beams” in the geometry-based sense of “horizontally-spanning members supported by vertical members.” The only ordinary beam-style load these members ever carried was their own weight, a little snow, and maybe some pigeon nests. These beams are there to provide bracing to the columns, to reduce the unbraced length that is vulnerable to buckling. In that role, they are loaded in compression or tension. The built-up box fatter-in-the-middle section is quite good as a compression strut. (Any section that works well in compression will be okay or better in tension.) So the shape makes sense.

But the Phoenix columns are also a good shape for compression members, so why not use that same section for the lower-tier braces? I can think of two reasons, one physical and one psychological. Physically, I’ve never seen a detail for connecting two Phoenix columns to one another. I’m sure such a detail must have existed, but it obviously was not a priority of the Phoenix Iron Works. Psychologically, these struts sure look like they should be beams.

You must be logged in to post a comment.