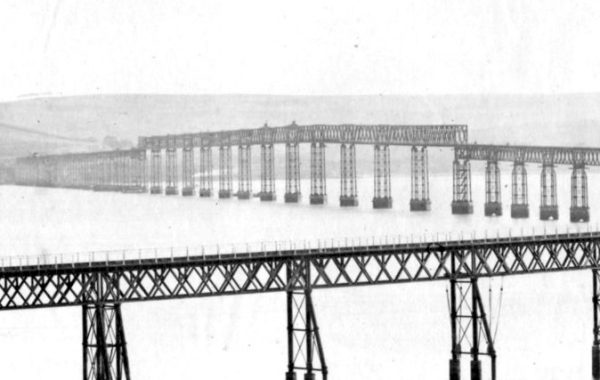

A view of some wood rafters held up by a header:

Each rafter has its own bridle iron as an end connection, which feels almost extravagant, although of course I wouldn’t say that if each rafter had a light-gage joist hanger, and joist hangers are the spiritual descendants of bridles. The iron straps are hooked over the top of the double header, and twist down to provide seats below the rafter ends. If these were level joists for a flat roof or a floor, that’s the whole story.

The rafters, being sloped, need sloped supports. And it’s very difficult to create bridles that have sloped seats. Each bridle starts off as a single piece of strap, heated and twisted until it reaches the desired three-dimensional U-shape-with-hooks. The bends for the seat are, as seen in the photo, at right angles to the long axis of the strap. Creating a sloped seat would mean making those bends at something like a 45-degree angle to that axis, which is a more delicate operation, more likely to go wrong. And if the angle is slightly off from the angle of the rafters, all the extra work is for nothing since the rafter still won’t sit properly on the seat.

The answer, of course, is shimming. Even flat joists are often shimmed when they sit on bridles because of slight geometric variations in both the wood and the iron that would create an unlevel floor if not shimmed. In this case, as can be seen, the shims take the form of wedges. The wedges seem to have been simply cut from pieces of wood similar to the rafters. The wedge nearest me when I took the picture feels like it’s installed upside down, although it really doesn’t matter. Using the wedges in this manner allows them to be crushed by uneven distribution of stress at the seat, leaving the rafter to sit on top unharmed.

And, no, I have no idea why there are toenails from the rafters to the header. Maybe as a temporary hold when this was all built about 110 years ago.

You must be logged in to post a comment.